Predicting Safe RTS following ACL Reconstruction

Introduction

Returning to sport (RTS) after an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is a critical phase where you clear the athlete to participate gradually to unrestricted participation. Unfortunately, high re-injury rates have been reported in the RTS phases. When in rehabbing someone after ACL reconstruction, you’ve probably held on to the Limb Symmetry Index (LSI) to evaluate someone’s strength gains. The most-used cut-off to evaluate strength is a comparison between the affected and non-affected leg is generally accepted to be an LSI ≥ 90%. This cut-off is widely recommended by consensus and expert opinions and serves as a target for the athlete to reach before returning to sport (RTS). However, using the LSI is arbitrary and has not been validated in a population undergoing ACL reconstruction. Hence, this review aimed to study the usefulness of the LSI in predicting safe RTS following ACL reconstruction in its ability to differentiate between athletes who safely return and those who sustain a second ACL injury.

Methods

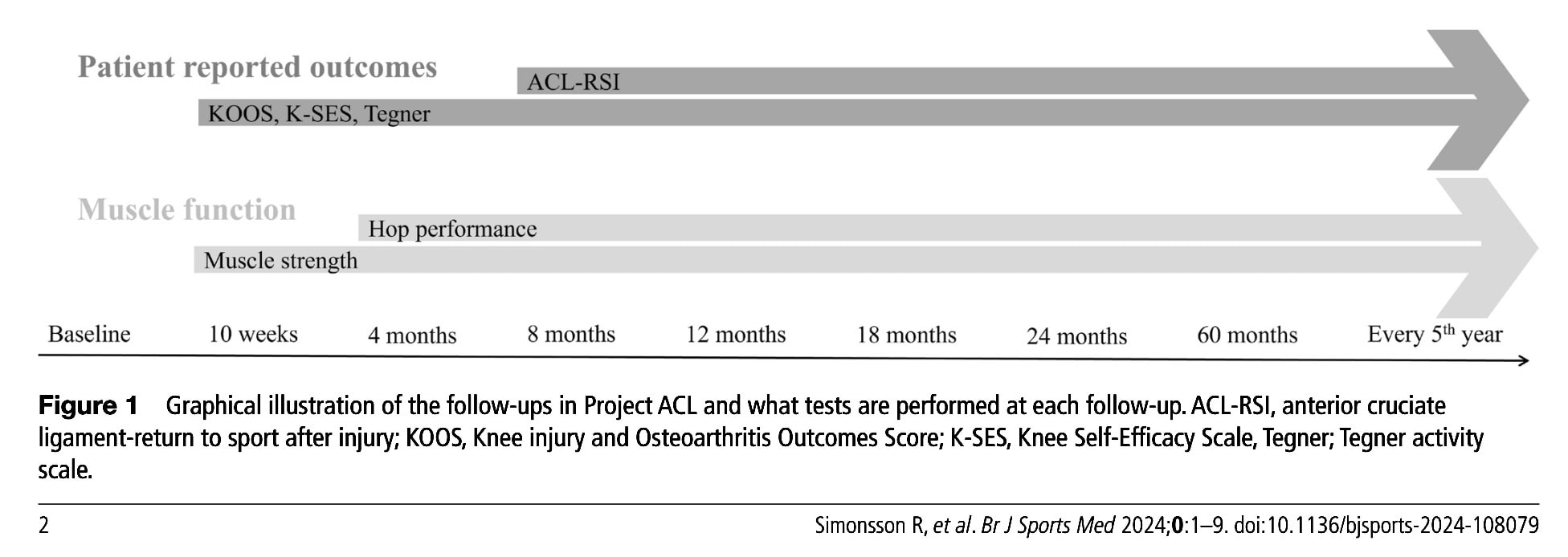

Data was gathered from an observational cohort study that prospectively followed patients in a Swedish rehabilitation registry (Project ACL). This registry allows people to enter their data following an ACL injury. The baseline is the ACL injury, and in case ACL reconstruction is performed, the baseline is adapted to the surgery date.

Patients who had sustained an ACL injury and were between 15 to 30 years of age were eligible for inclusion.

Functional testing included:

- Muscle strength was evaluated using data obtained from unilateral isokinetic knee extension and flexion from a dynamometer.

- Hop tests were performed according to the hop test cluster by Gustavsson:

- Vertical hop: measuring the flight time and conversion to height of the jump in centimeters

- Hop for distance: Participants jumped as far as possible and distance is measured from to at take-off to heel at landing.

- 30-second side hop: over 2 parallel strips separated by 40 centimeters.

All patients in the Registry filled out the following patient-reported outcome measures:

- The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcomes Score (KOOS)

- The Knee Self-Efficacy Scale (K-SES)

- On a standardized scale, the Tegner Activity Scale measured the participant’s activity level before and after sustaining an injury. Eligible candidates had a preinjury Tegner score of at least 6. This score of 6 and above indicates that the patient participates in pivoting sports.

- The Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Return to Sport after Injury (ACL-RSI)

The registry tracks performance tests and patient-reported outcomes over time, as can be seen in the picture below.

At each follow-up, patients are asked whether or not they sustained a second ACL injury. The primary outcome of interest was a safe RTS following ACL reconstruction. This was defined as not sustaining a second ACL injury within two years.

Further, the authors also looked into the following:

- Cut-off values for each functional test that differentiates between safe RTS and no safe RTS, including how well passing the test battery with the new cut-offs could differentiate

- How well can predefined LSI cut-offs ranging between 80-90% LSI differentiate?

Results

233 athletes with an ACL injury were included, of which 119 were women and 114 men. Their age at the ACL injury was 20.5 years. Their mean Tegner level was 9, indicating that they participated in sports such as football. The mean RTS time was 14.2 months (+/- 10.1 months). Thirty-seven (16%) athletes had not safely returned to the same Tegner activity level of sport since they sustained a second ACL injury within 2 years after their RTS. The majority (65%) of the second ACL injuries were on the same side.

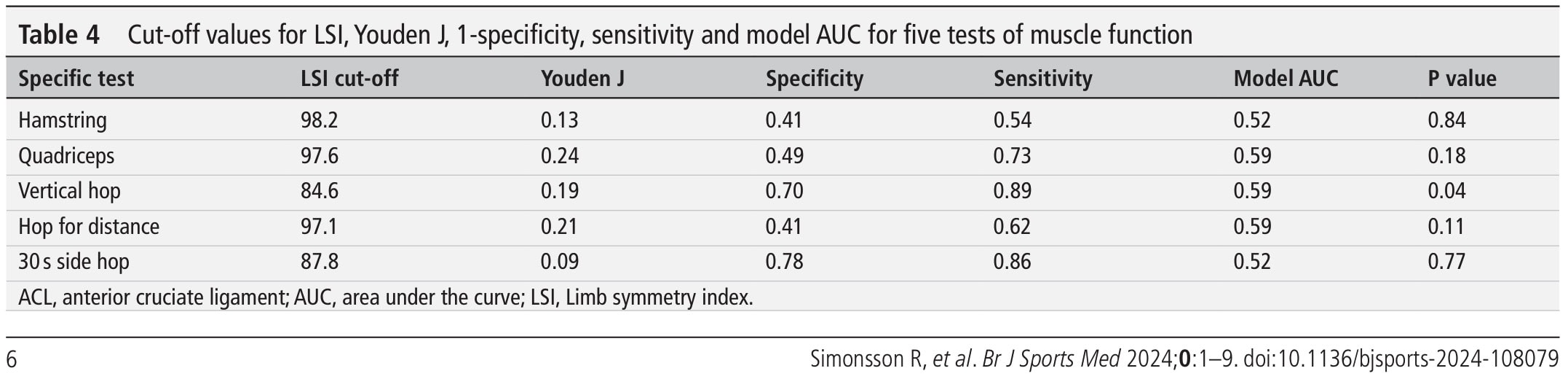

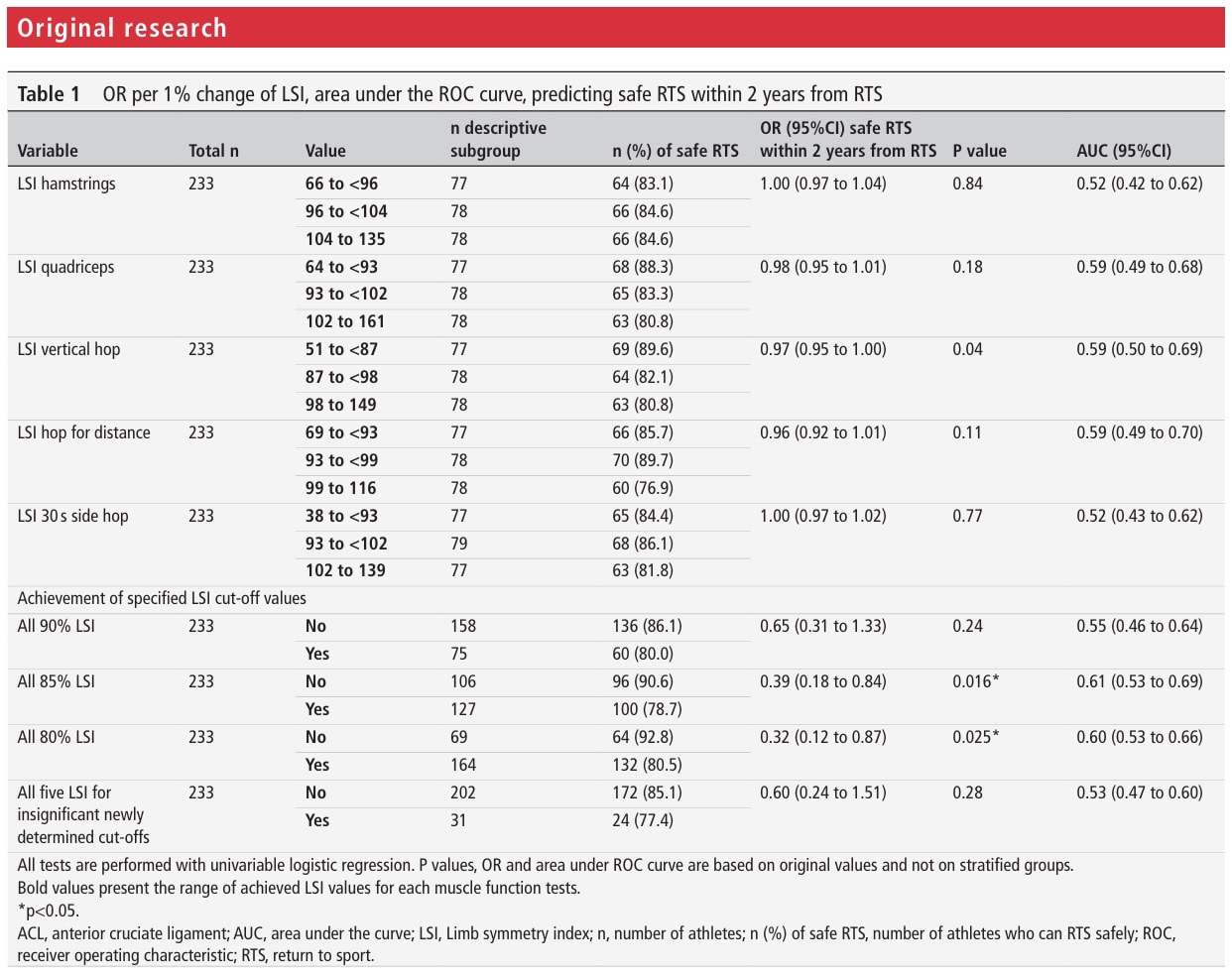

This paper defined new cut-offs that best differentiate between athletes with a safe RTS following ACL reconstruction and athletes with a second injury. The vertical hop test with an 84.6% LSI cutoff was a significant discriminator between athletes with a safe RTS and those with a second injury. However, the Youden J, which is a measure of test performance, and the Area under the curve (AUC) were low, indicating poor differentiation.

Despite only one of these 5 functional tests achieving significance, 77% of athletes passing all 5 newly defined cut-off values had a safe RTS following ACL reconstruction. When the generally accepted 90% LSI is used, 80% of athletes passing this requirement had a safe RTS.

Athletes passing 80 or 85% LSI had lower odds of having a safe RTS (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.87 p=0.025 and OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.84 p=0.016, respectively). However, here also the AUC indicated poor predictive capacity. There was no significant association between passing the 90% LSI and having a safe RTS following ACL reconstruction.

Questions and thoughts

Should we now let go of the LSI as a measure to define athlete readiness to RTS? Not in my opinion, if we take into account that the absolute values of the non-injured leg should also be monitored. Since deficits in the contralateral (non-ACL injured) limb can overestimate the LSI, this is something to look out for during the rehabilitation process. Of course, you want someone to achieve perfect left-right symmetry. Hence you should always aim to achieve high symmetry, but when you understand that the LSI can be overestimated, you’ll understand that achieving a 90% LSI is not everything you need to clear an athlete.

Moreover, it’s not just about physical readiness. You can not overlook someone’s confidence and psychological readiness when clearing someone. Physical and psychological readiness to RTS are mutually intertwined. Neglecting someone’s doubts and fears, leading to on-field avoidance of certain movements may even put the athlete at a higher risk of re-injury, despite having a perfect physical readiness in controlled situations like when passing the RTS test in physiotherapy practice. Therefore, on-field rehabilitation should follow the controlled rehabilitation phases. When clearing someone to RTS, make sure you have evaluated the psychological readiness, for example using the ACL-RSI, TSK-11, Tegner-Lysholm, and IKDC questionnaires.

Targeting a satisfactory neuromuscular activation of key muscles surrounding the knee joint is equally important. Zunzarren et al. (2023) showed that deficits in neuromuscular activation following ACL reconstruction can persist for over 3 years. They used a scoring system “Biarritz Activation Score – Knee” to document differences in activation between left and right.

Talk nerdy to me

A major limitation of this study is that concomitant injuries were not recorded. As ACL injuries are often a combination of (sports)traumata, lesions to other structures around the knee are common (Farinelli et al. 2023). These injuries often encompass the menisci, ligaments, cartilage, and require different treatment approaches and timeframes (Hamrin Senorski et al. 2018). Another relevant limitation to consider is the fact that the absolute strength values were not taken into account. Hence, lower contralateral strength due to decreased sports participation, for example, can overestimate limb symmetry, and as the absolute strength values lacked, the clinical usefulness of the calculated LSI is not hundred percent reliable.

The findings indicate that much more is necessary to clear an athlete to RTS. Respecting the time needed for proper tissue healing and regeneration and delaying the RTS to 9 months at least can significantly reduce reinjury risk (Grindem et al. 2016). Assessing beyond functional tests to have a broader understanding of someone’s mental readiness is essential. Yet, this alone does not explain everything neither. Zarzycki et al. (2024), for example, found that female athletes with better psychological readiness had a higher risk of sustaining a second ACL injury. They also returned earlier than those who had a safe RTS. Again, this points to the importance of proper counseling and educating athletes about the importance of respecting the rehabilitation process and its timeframes. Including a more continuous follow-up instead of a one-time clearance test, can also be helpful in guiding the returning athlete.

Take-home messages

This study highlights the absence of a predictive relationship between achieving 90% LSI in functional tests and being able to safely RTS. The LSI recommendations based on expert consensus alone are not sufficient to clear someone to RTS, but instead this decision should be based on a combination of functional testing, field testing, psychological readiness, and the effect of time allowing good tissue healing should all be combined.

Reference

LEARN TO OPTIMIZE REHAB & RTS DECISION MAKING AFTER ACL RECONSTRUCTION

Sign up for this FREE webinar and top leading expert in ACL rehab Bart Dingenen will show you exactly how you can do better in ACL rehab and return to sport decision making