Insertional Achilles Tendinopathy: The Effect of Reducing Tendon Compression

Introduction

Achilles tendinopathy is common and is classified as insertional or midportion tendinopathy. While midportion tendinopathy is more responsive to exercise therapy, insertional Achilles tendinopathy can be stubborn to treat. Cook et al. (2012) proposed that compression might be the underlying factor leading to less optimal outcomes after exercise therapy for insertional Achilles tendinopathy. While this paper comes with sound rationale, no studies have yet shown this to date. Therefore, the aim of this randomized controlled trial was to investigate the effectiveness of a low tendon compression (LTCR) versus a high tendon compression rehabilitation (HTCR) program.

Methods

In this randomized controlled trial, sport-active individuals between 18 and 60 years were included when they suffered from chronic (>3 months but under 3 years) insertional achilles tendinopathy. To be eligible for participation, they had to have a score of 80 or less on the VISA-A questionnaire, and they had to engage in running-based sports at least twice per week.

The diagnosis of insertional Achilles tendinopathy required a positive palpation at the insertion on the calcaneus and the reproduction of pain during the single-leg-hop test. Using ultrasonography the presence of intratendinous hypoechoic changes and/or tendon thickening and/or the presence of intratendinous vascularization through power Doppler was also required. Lastly, weight-bearing lateral radiographs were taken to evaluate the presence of bone abnormalities like a Haglund deformity, but in case of an abnormality, the subject was still eligible for inclusion.

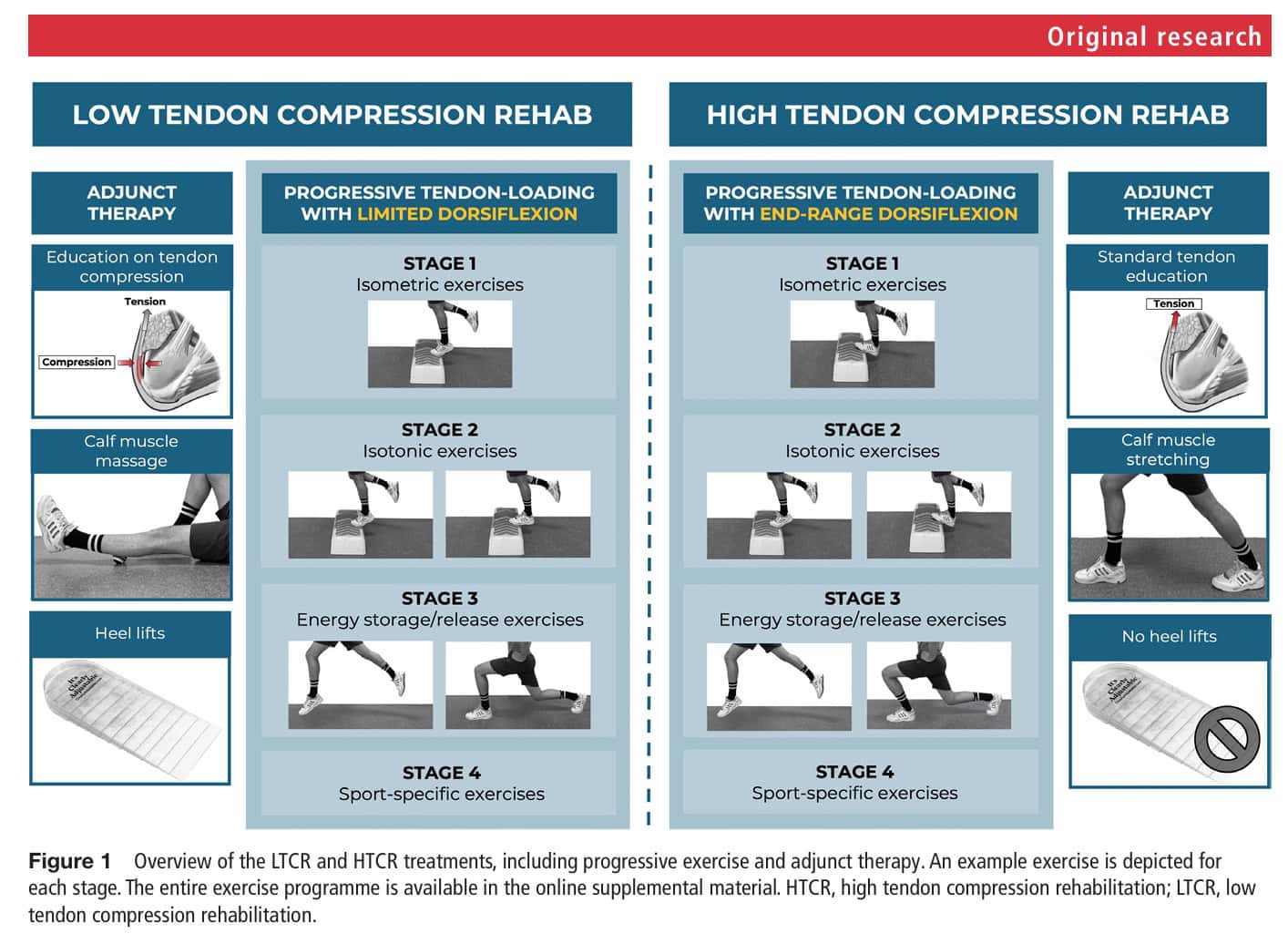

The authors designed the LTCR program so that the compression on the Achilles tendon insertion at the calcaneus was minimized by avoiding positions of dorsiflexion throughout the rehabilitation. The comparator intervention was a high compression variant. Participants were randomly allocated to either the LTCR or HTCR rehabilitation programs, performing the program supervised by the physiotherapist and at home. Both groups participated in a similar structured progressive exercise plan, but the main components differed.

The structure of both programs was similar:

- Stage 1: Isometric exercises at 50% of the maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC): 5 repetitions of 30 seconds, progressing to 5 repetitions of 60 seconds at 70% MVIC.

- Stage 2: High-load isometric exercises of stage 1 every first day and new isotonic exercises the second day. The isotonic exercises started with 4 sets of 15 repetitions at 65% of the 1-repetition maximum (1RM) and progressed to 4 sets of 6 repetitions at 85% of the 1RM.

- Stage 3: High-load isometric exercises every first day, high-load isotonic exercises every second day, and energy-storage and release exercises every third day (starting with 3 sets of 10 repetitions at 75% of 1RM and progressing to 3 sets of 6 repetitions at 85% 1RM).

- Stage 4: running and jumping exercises every second or third day, with high-load isometric exercises on the other days.

The LTCR, however, performed the program without tendon compression, by avoiding ankle dorsiflexion, while the HTCR group did all the exercises in end-range ankle dorsiflexion.

Progression criteria were made based on the following:

Pain remained less than 5/10 NRPS both during exercise and 1 hour after completion and the following morning, andThere was no increase in average pain and stiffness from week to week, andParticipants had completed at least 2 weeks in every stage, and at least 1 week of high-loading exercises

During their participation in this RCT, the participants were asked to avoid tendon-loading sports during stages 1-3. The minimum time to return to sports was 8 weeks. During the return to sports phase, participants were instructed to perform maintenance exercises from stages 1 and 2 two times per week.

Key differences between the groups:

In the LTCR group, exercises were performed with limited ankle dorsiflexion, and in the HTCR group, exercises were performed in end-range dorsiflexionWhile the LTCR group performed daily self-calf muscle massage using a hard ball, the HTCR group was instructed to stretch the calf daily. In the LTCR group, participants received adjustable heel lifts, the height of which was gradually reduced during phase 4, while the HTCR group did not receive those heel lifts.Furthermore, both groups received education on insertional Achilles tendinopathy, covering the pathology itself, the relationship between tendon load and pain, the benefits of progressive exercise therapy for improving the load-bearing capacity of the musculotendinous unit, and the importance of pain monitoring. Additionally, in the LTCR group, extra information regarding the role of compression in the pathogenesis of insertional Achilles tendinopathy was provided along with expressing the importance of reducing this load during rehabilitation.

The primary outcome of interest was the 0-100 VISA-A questionnaire at 12 and 24 weeks. The minimal clinically important difference was established at 10 points.

Results

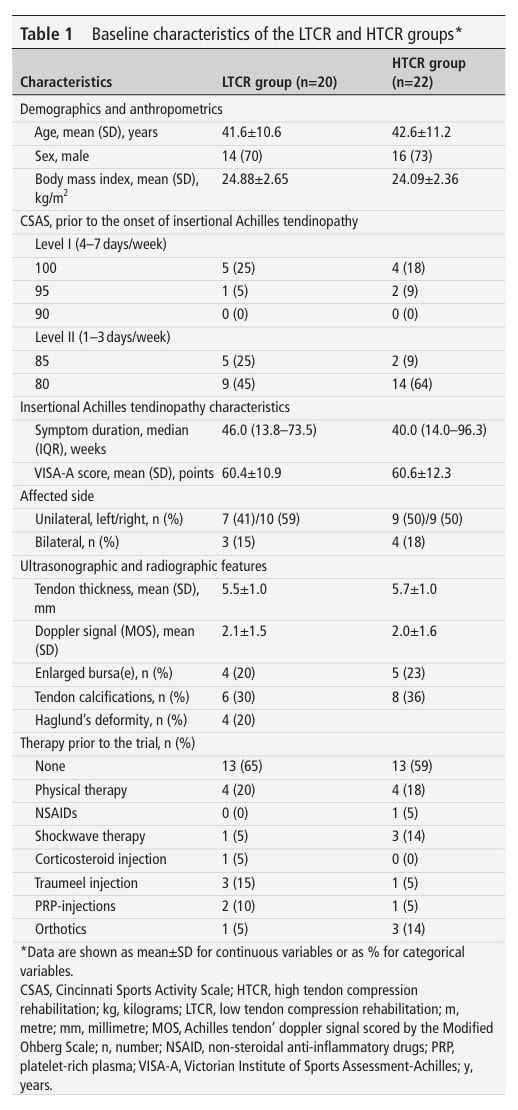

A total of 42 patients were included and 20 of them were allocated to the LTCR group and 22 to the HTCR group. They had an average age of 41.6 and 42.6 years, and 70% of the population was male. The average symptom duration was 46 weeks in the LTCR and 40 weeks in the HCTR groups, respectively. The main VISA-A score at baseline was 60.4 in the LTCR and 60.6 in the HTCR groups, respectively. Most of them (around 60%) had no prior treatments, and about 20% of the population had tried physiotherapy before.

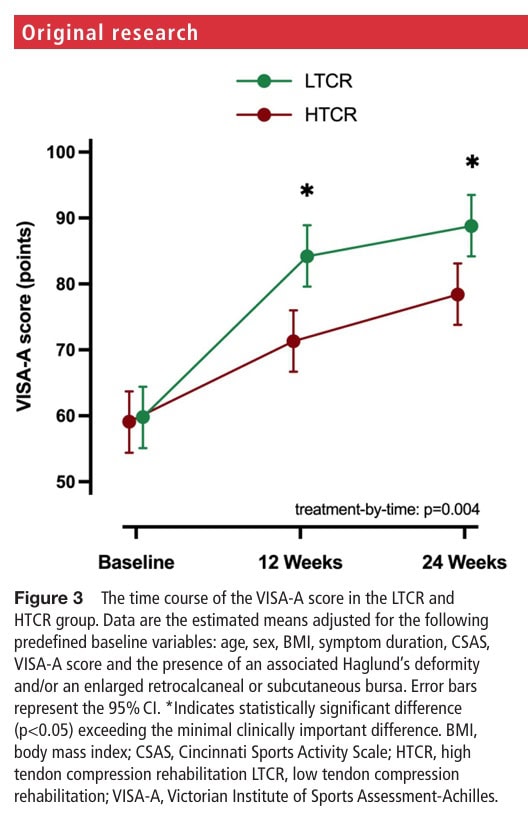

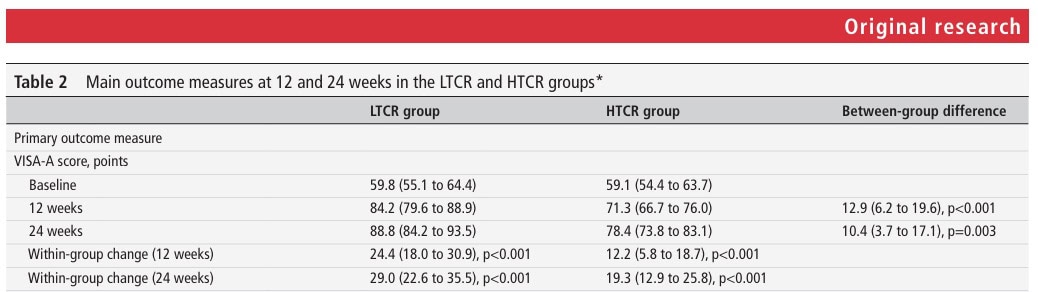

The analysis of the primary outcome revealed a significant interaction effect, indicating a significant between-group difference. There was an improvement in insertional Achilles tendinopathy severity, as documented by an increase in the VISA-A in both groups. In the LTCR group, the score improved from 59.8 to 84.2, and in the HTCR group from 59.1 to 71.3, leading to a significant between-group difference of 12.9 points at 12 weeks in favor of the LTCR group.

The effect was retained over the 24 weeks: the LTCR group further improved to 88.8, while the HTCR further increased to 78.4, leading to a between-group difference of 10.4 points, also in favor of the low tendon compression group.

Questions and thoughts

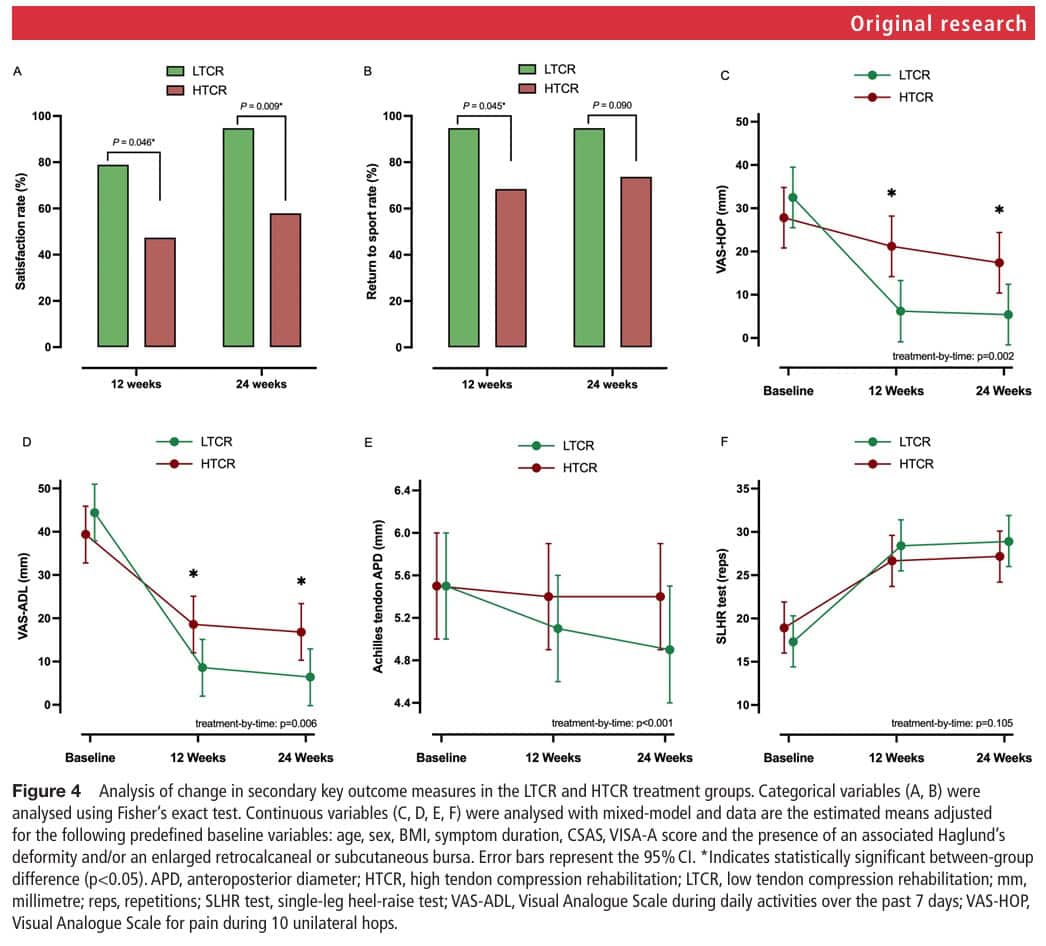

The lower limit of the between-group difference confidence intervals reveals values below the MCID, indicating that the observed effect is still uncertain. When looking at the secondary outcomes, the LTCR group showed more satisfaction and a higher return to sports rate, despite the same exercise adherence found between the groups.

The magnitude of the effect was greatest in the first 12 weeks, and this effect plateaued between 12 and 24 weeks. The tendons were progressively loaded in the first 12 weeks, and after 12 weeks, the exercise program stopped. It might be reasonable to say that extending the period of the progressive loading might enhance the observed outcomes.

Moreover, ultrasound evaluations showed that only the LTCR group experienced a significant decrease in tendon thickness after 24 weeks. The authors suggest that since eliminating the compression component during rehabilitation is less provocative, it could desensitize the Achilles tendon which in turn facilitates recovery of load capacity. At the same time, the tensile loads exerted on the tendon during the LTCR group’s rehabilitation program lead to a cascade of effects in which fibracartilaginous metaplasia leads to lower glycosaminoglycan and proteoglycan synthesis, which in turn reduces fluid accumulation in the tendon.

Talk nerdy to me

Something to keep in mind is that we are not sure which intervention component led to the significant differences in favor of the LTCR group. Since the LTCR group, unlike the HTCR group, also received heel raises and calf massage using a therapy ball, the combination of interventions may have influenced the effect that now emerges primarily as a result of the modified exercises themselves. Further studies could investigate the effect of the elimination of ankle dorsiflexion alone. Study participants indicated they found the interventions credible, regardless of being in the LTCR or HTCR group, and expected to benefit from them, so their expectations did not confound the outcomes.

Generalizability of the study’s findings is limited to sport-active participants. Also, the current study population had chronic insertional Achilles tendinopathy, lasting at least 3 months, so transferring this effect to acute tendinopathy is not valid.

Recently, a new questionnaire emerged: the TENDINopathy Severity assessment–Achilles (TENDINS-A). In contrast to the VISA-A, which lacks construct and content validity, the TENDINS-A was found superior on terms of both construct validity and excellent reliability. The main patient-reported outcome measure for evaluating disability in individuals with Achilles tendinopathy is therefore recommended to be the TENDINS-A (Murphy et al., 2024).

Take-home messages

By eliminating ankle dorsiflexion and thus the compression component during exercises, this trial showed an effective strategy for improving insertional Achilles tendinopathy. This effect was sustained after 24 weeks, although the lower limit of the confidence intervals pointed to an unclear effect. Using heel lifts, and avoiding calf stretching and ankle dorsiflexion throughout the rehabilitation, the compression on the insertion of the Achilles tendon is eliminated. By progressively loading the tendons through 4 stages, load-bearing capacity is gradually restored.

Reference

WHAT TO LOOK FOR TO PREVENT HAMSTRING, CALF & QUADRICEPS INJURIES

Whether you’re working with high-level or amateur athletes you don’t want to miss these risk factors which could expose them to higher risk of injury. This webinar will enable you to spot those risk factors to work on them during rehab!