Assessing Running Readiness - The Road to Decreasing Injury

Introduction

Runners and track and field athletes face injuries frequently, most of which are overuse injuries in the lower limbs. Until now, only mixed results have emerged from several movement screening tools, and a general remark is that the generic approach for assessing running readiness is not valid for running-specific sports. Recently, the Running Readiness Scale was developed by Harrison et al. 2021 and later recommended in a clinical commentary for running rehabilitation. As it is specifically designed for runners and has shown promising results regarding the correlation of the score with running kinematics, the Running Readiness Scale is now evaluated for its ability to predict injury.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, NCAA Division III cross country and track & field athletes in running, jumping, and vaulting were included. They were uninjured and free of any symptoms. All data regarding pre-season training and prior sports-related injuries were collected at baseline, along with their demographic variables to control for eventual confounders. Assessing running readiness was done using the Running Readiness Scale.

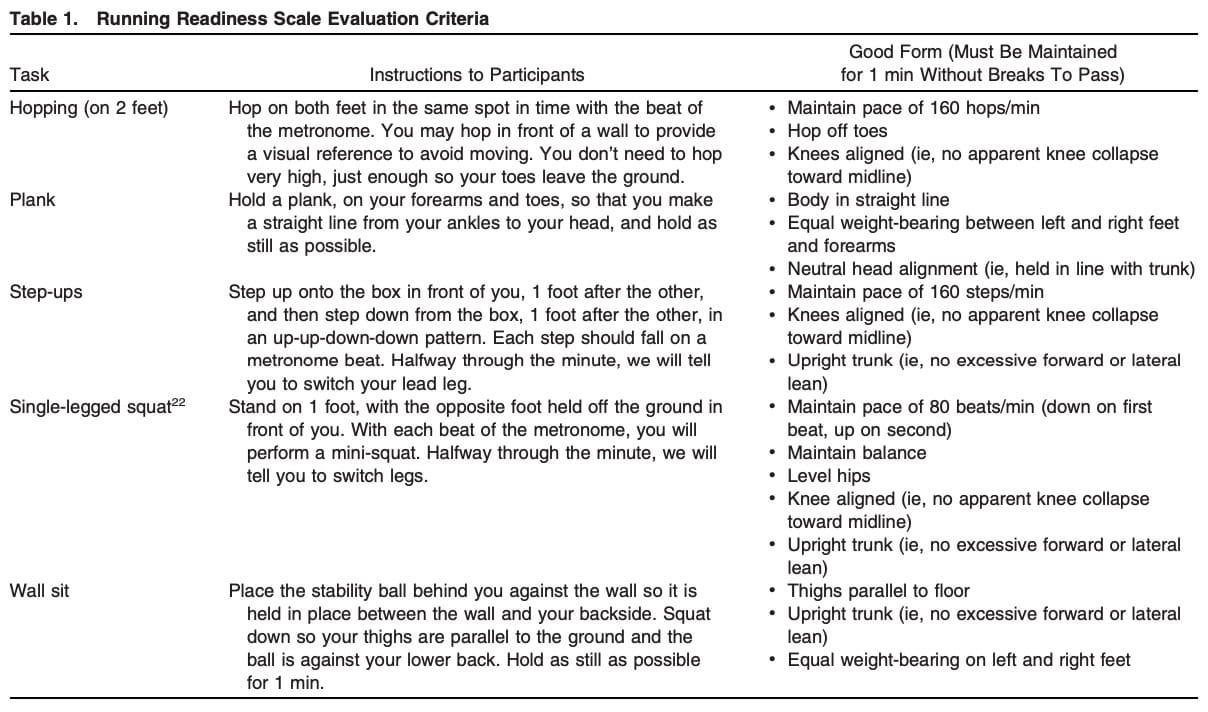

The Running Readiness Scale consists of 5 tasks, each performed for 1 minute with 30 30-second rest in between

- Double-leg hopping on the rhythm of a metronome set at 160 beats per minute (bpm)

- Plank

- 6” step-ups*, following the rhythm of a metronome at 160 bpm

- Single-leg squats*, following 80bpm on the metronome (down on one beat, up on the next beat)

- Wall sit

* The step-ups and single-leg squats were performed for 30 seconds on each leg.

The tasks from the Running Readiness Scale were evaluated for their execution, following the criteria in the table listed below:

For every task performed successfully, 1 point was awarded, so that the total scores on the Running Readiness Scale ranged from 0-5.

The athletes were followed over the course of their season, and every sports-related injury of the lower limb that prevented the athlete from participating in a practice session or a meet was recorded, along with the mechanism of injury and related variables.

Results

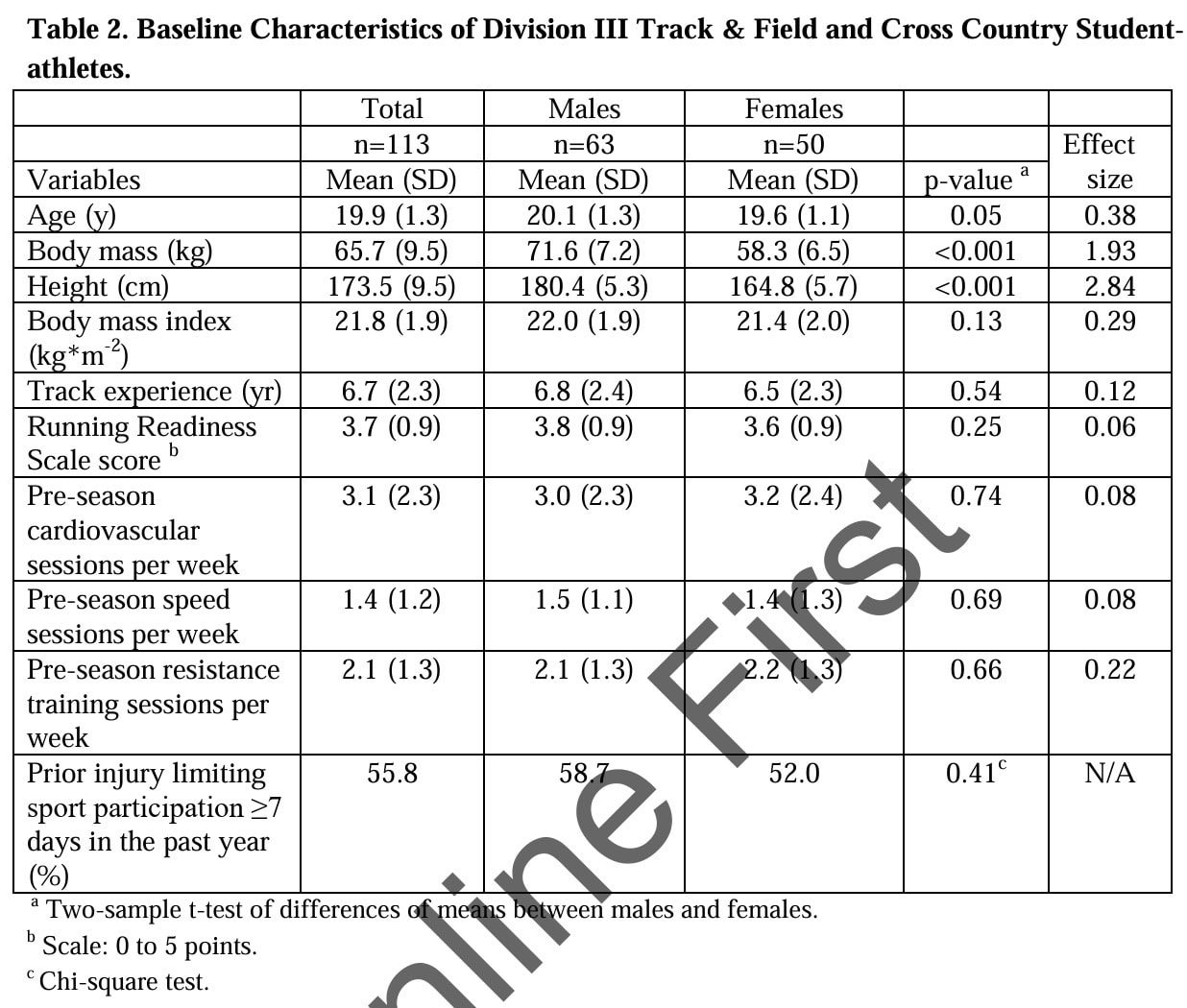

In total, 113 athletes were enrolled in the cohort study, of which 63 were males and 50 were females. At baseline, they reported equal characteristics except for the males being taller and heavier.

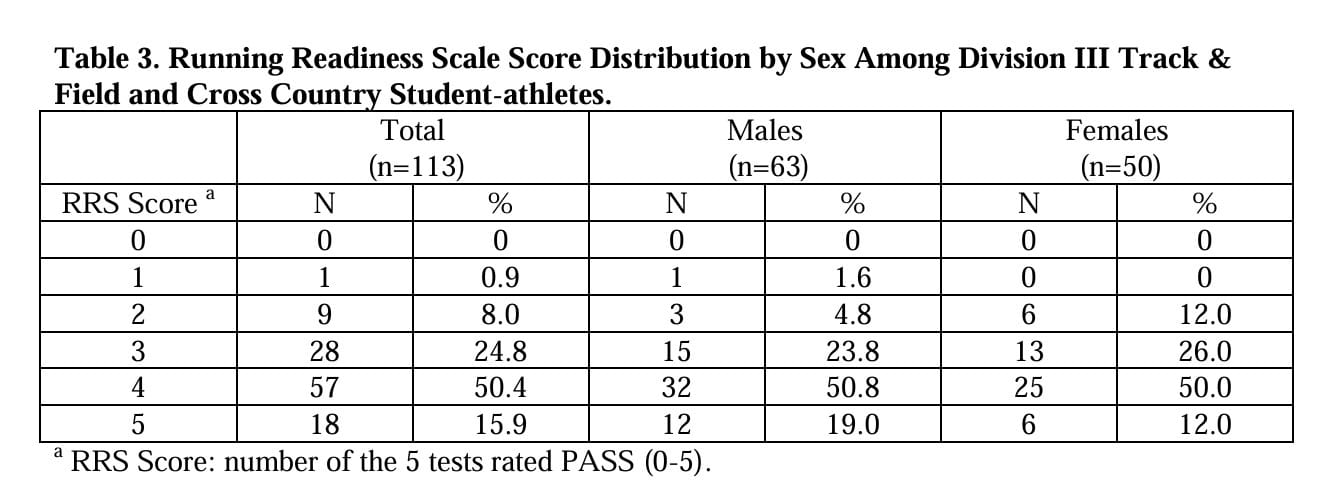

Most of the athletes passed 4 out of 5 items on the Running Readiness Scale.

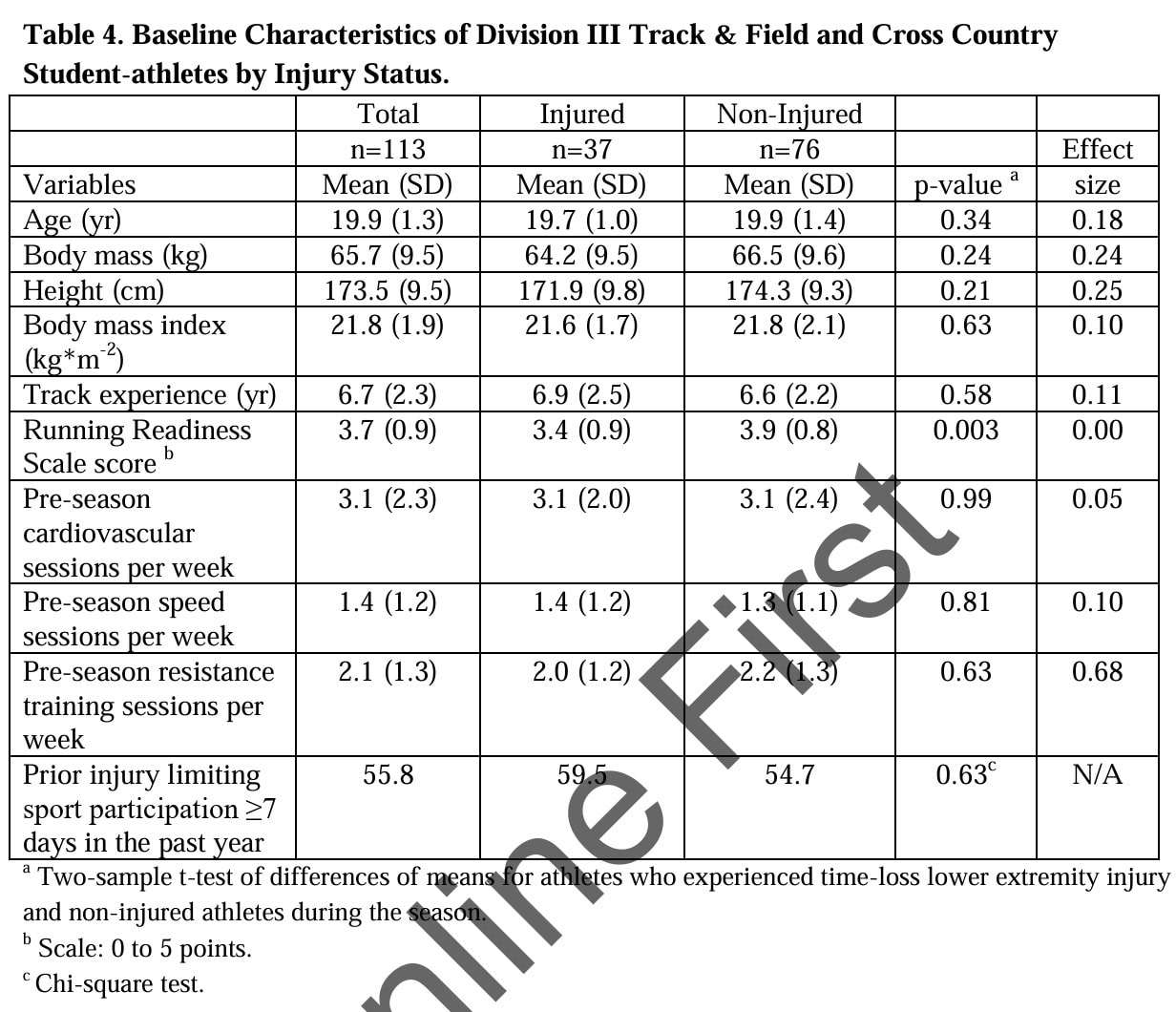

During the season 37 athletes got injured to the lower limb. A significant difference between the injured and non-injured athletes regarding their scores on the Running Readiness Scale emerged. Injured athletes scores’ were significantly lower and this difference remained after controlling for potential baseline confounders.

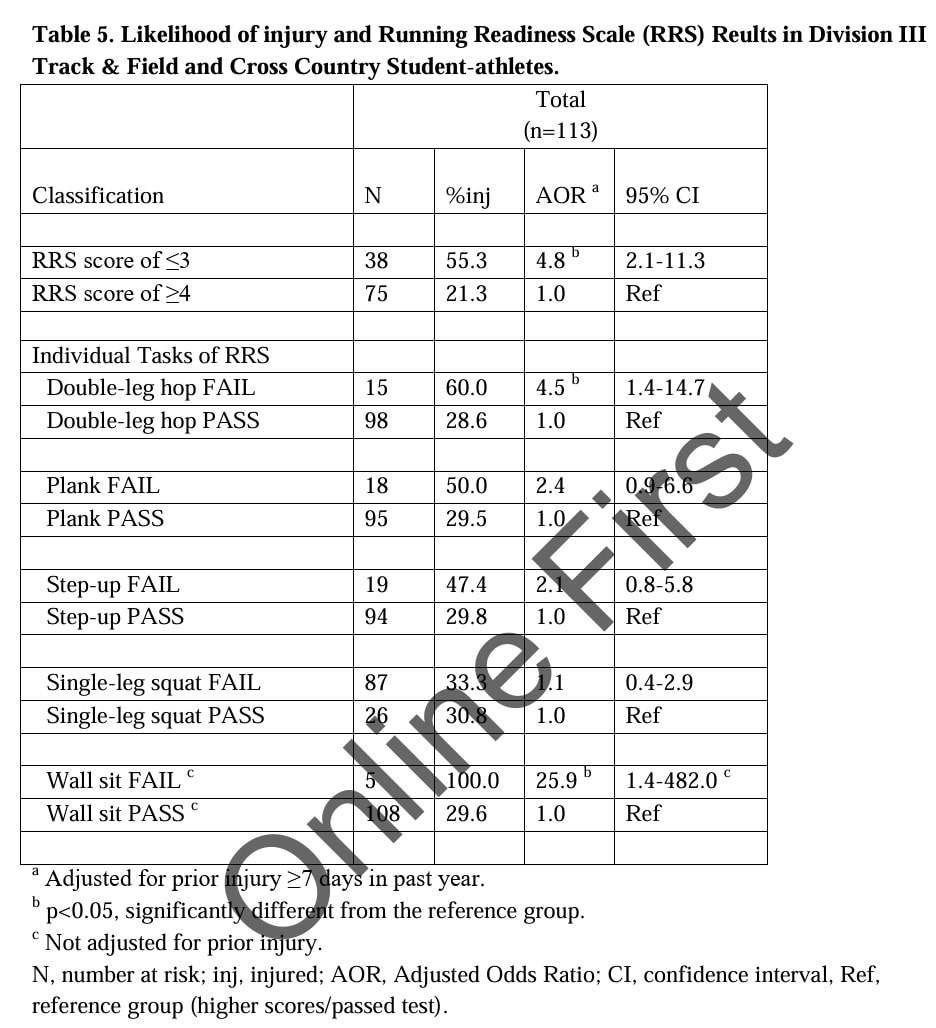

It was calculated that athletes who scored 3 points or less on the Running Readiness Scale were almost 5 times more likely (OR=4.8, 95%CI: 2.1 to 11.3) to experience a lower extremity injury during the season compared to athletes achieving a score of 4 or 5. Looking at the tasks of the Running Readiness Scale individually, failing the double-leg hop (OR=4.5, 95% CI 1.4 to 14.7) and the wall sit (OR=25.9, 95%CI 1.4 to 482) were the most important predictors of sustaining an injury.

Questions and thoughts

Double-leg wall sits have been replaced by unilateral wall sits in other studies, and since the confidence interval was very wide, this may be a viable option to refine the Running Readiness Scale even more, since the unilateral version adds more control and balance demands.

The single-leg squat was not predictive of injury, but this is possible because no minimum height was defined. This could possibly have allowed participants to choose their own squat depth, and by avoiding deeper bends, weaker participants probably outsmarted the researcher. Deeper movements to a pre-defined minimum might have caused more participants to fail on this part.

Using dichotomous criteria (Pass or Fail) per test simplified the analyses, but makes one have to draw a line for a movement that may be variable. Furthermore, we have no information on what angle the movements were observed from, which may also have caused variability in the results. On the other hand, the use of the individual tasks from the Running Readiness Scale have previously shown good potential for assessing movements relevant to the development of running-related injuries.

While the standardized assessment is an important strength of this study, we must acknowledge that even a standardized assessment can be subject to interpretation and observation. Especially since this study showed moderate to poor interrater reliability, this can be the case here. Visual observations can potentially be enhanced using certain apps and good training. Nevertheless, using a set of criteria is crucial to start with. I suggest only one assessor to evaluate follow-up athletes from a certain team to reduce the possibility of finding interrater differences.

Talk nerdy to me

These data were collected prospectively, avoiding measurement bias. The analyses were controlled for the influence of confounding variables, but the conclusions stood. We should keep in mind that perhaps not every athlete reported injuries. I imagine that busy seasonal schedules and not wanting to miss selections may have gotten in the way of accurate reporting. It is also possible that athletes developed symptoms but continued training without reporting injuries. Since only time-loss injuries were analyzed in this model, the Running Readiness Scale should be viewed more as a guide for training and adjustment, as unreported injuries and injuries without time-losses may underestimate the observed effects, while ultimately having a good chance of leading to time-loss injuries.

Wide confidence intervals, especially for the wall sit can be potentially caused by the fact that a varied study population was included. More homogeneous groups of athletes can be studied in the future to seek whether some tests are more relevant in different sport specializations.

Take-home messages

Scoring 3 points or less on the Running Readiness Scale puts an athlete at risk of injury in the season, regardless of training status, earlier injuries and other confounders. The most important contributors of the risk were failing the wall sit and double-leg hopping tests. Interrater reliability was moderate to low, indicating that one observer should ideally conduct all the tests and sufficient training in scoring the individual items should be organized. Nevertheless, this set of criteria assessing running readiness can help pre-season training adjustments to be made to minimize the risk of sustaining lower limb injuries in an athlete sample.

Reference

LEVEL UP YOUR DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS IN RUNNING RELATED HIP PAIN - FOR FREE!

Don’t run the risk of missing out on potential red flags or ending up treating runners based on a wrong diagnosis! This webinar will prevent you to commit the same mistakes many therapists fall victim to!