Early versus delayed lengthening exercises for acute hamstring injury in male athletes

Introduction

Based on a recent review including 11 randomized controlled trials, eccentric exercises have been found to lead to faster return to sport and lower reinjury rates. This is a very important finding as acute hamstring injuries significantly contribute to days lost from sports and high and frequent reinjury rates. But when is the best time to introduce lengthening exercises into the rehabilitation of acute hamstring injuries? This study looked at the effect of timing of the introduction of eccentric exercises. Can early lengthening for hamstring injuries influence the time to return to sport?

Methods

A single-center parallel-group superiority trial was conducted at the Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital. Male athletes between 18-50 years with an acute MRI-confirmed hamstring injury were included. Possible candidates with a previous hamstring injury in the last 6 months or chronic (>2 months) hamstring problems and complete ruptures/avulsions (Peetrons classification grade III) were excluded.

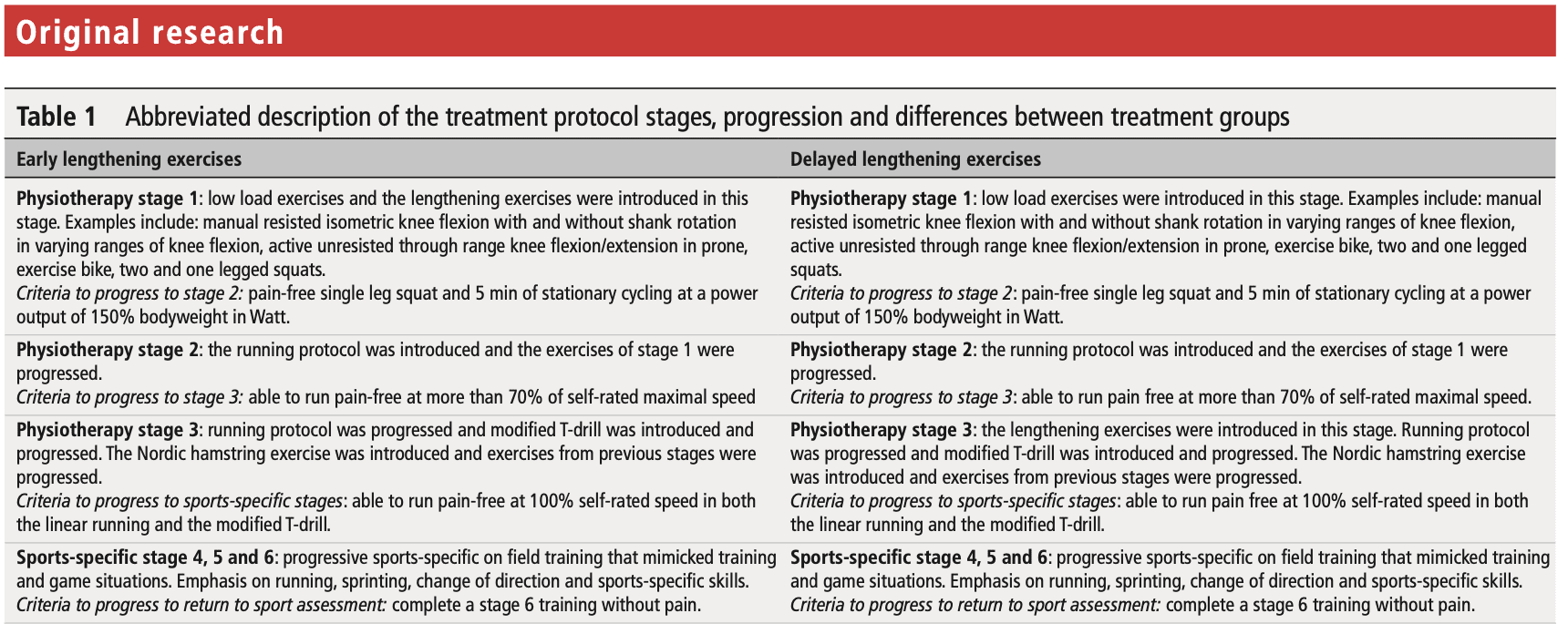

Both groups followed a standard criteria-based rehabilitation program that consisted of 6 stages: 3 physiotherapy-based stages and 3 sports-specific stages. The groups differed in the timing of the introduction of the lengthening exercises. In the early lengthening group these were started on the first day of rehabilitation, while in the delayed group the lengthening exercises were introduced after meeting the criteria of being able to run at more than 70% of self-rated maximal speed.

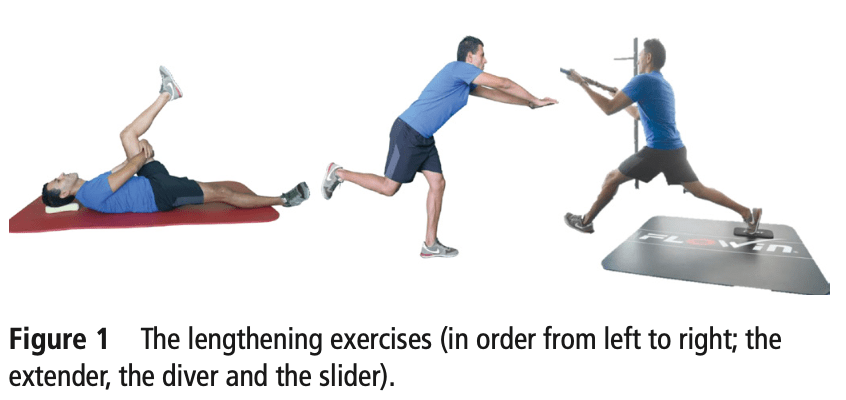

The lengthening exercises consisted of the extender (performed daily), the diver ( every second day), and the slider (every third day). Other exercises consisted of bilateral and unilateral squats and bridges, supine isometric heel digs, manually resisted exercises, prone leg curls, and Nordic hamstring exercises. The primary outcome assessed in this study was the time to return to sport, which was defined as “the number of days from injury until full unrestricted training and/or match play”.

Results

Eighty-eight participants were included and equally divided into the early and delayed lengthening group. The early group began with the lengthening exercises on the first day of rehabilitation and this was after a median of 5 days post-injury (range 3-6 days). In the delayed group, the first rehabilitation session with the lengthening exercises was only introduced after 16 days post-injury (median range 11-23 days) and this was 12 days post-injury at median (range 7-19 days).

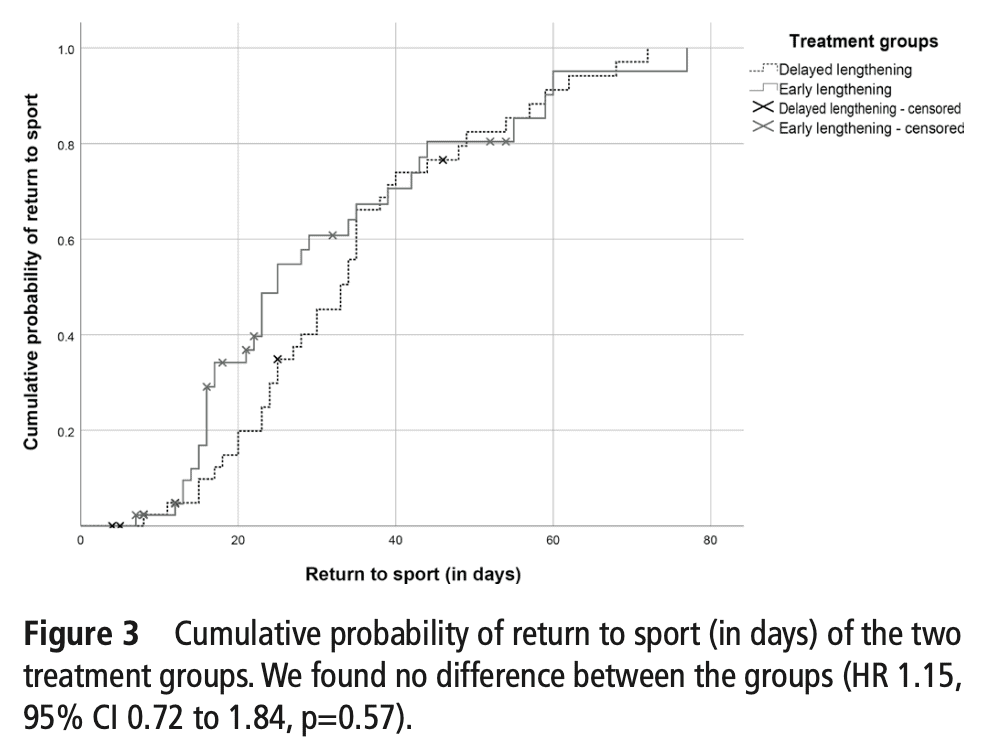

The median return to sport was after a median of 23 days (range 16-35) and 33 days (range 23-40) for the early and delayed lengthening groups respectively. The median difference between both groups was 8 days (range 0-14 days). The cumulative probability of returning to sport is depicted below. As you can see, no clear differences between the groups emerge as the curves are not separated from each other and overlap frequently.

In a secondary analysis, reinjuries were compared between the early and delayed hamstring lengthening program at 2, 6, and 12 months. The odds ratios, however, did not attain the significance level.

Questions and thoughts

So what do you conclude based on the results? There was no significant difference between the early and delayed hamstring lengthening program. Thus early lengthening for hamstring injuries did not improve the time to return to sport compared to the delayed initiation. Nor did it improve the risk of re-injury. The median difference in time to return to sport was 8 days with a range of 0-14 days, but this was not significant. This means that at worst, the participants performing early lengthening for hamstring injuries return at the same time as the participant delaying the lengthening and at best, they return 14 days faster. As no differences were found in the reinjury rates between both groups, I would rather start right away with the lengthening exercises in those with acute hamstring injuries. At best, you get your athlete to return to sports faster, and at worst, you return them at the same time. Beginning the lengthening exercises early on in the rehabilitation may also increase the athlete’s confidence in the performance of heavier eccentric exercises later on in progressions made. So why not? Relevant here also is the following. With only two days (range 1-4 days), the median time to MRI after injury was kept very short. This will not be possible in every clinical setting as waiting times are often much longer. But, if your patient only comes in after he or she has had an MRI that comes much later after the injury than was the case in this study here (often weeks after), I don’t think it would be necessary to delay the eccentric extension exercises any longer.

Talk nerdy to me

Cohen’s d for the median between-group difference of 8 days equaled 0.39, representing a small effect size. The effect size calculation was based on the mean return to sport time for athletes with acute hamstring injuries from earlier studies in the Aspetar study center (mean 25.4 days). In their power calculation that was done beforehand, they opted for a small effect size of 25% as this corresponds to approximately 6.6 days, which means one extra match played in most sports. This seems reasonable to opt for a small effect size in this case as the mean return to sport in their previous research was only 25 days. Keeping realistic time frames in mind, 25% of 25 days on average seems a reasonable timeframe.

It was prespecified that significant baseline characteristics were adjusted in case they changed the outcome by more than 10%. As the ‘time of injury during match or training’ differed significantly between the groups, the primary outcome analysis was adjusted. In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio was 1.15 and the adjusted analysis revealed a hazard ratio of 0.95, both insignificant. Also, this adjusted analysis showed that there was no difference between those players who injured themselves early on in match play or training versus those who sustained the acute hamstring injury later on in the game.

For the primary analysis, the participants lost to follow-up were censored. However, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to test the robustness of the treatment effect. The sensitivity analysis was conducted with a worst-case scenario in mind; any person lost to follow-up may not have returned to sport. This analysis revealed that the hazard ratio changed from 0.91 to 0.82.

Unfortunately, no subanalysis was made looking at differences in injury severity. Therefore, no recommendations can be made here. It would be interesting to see if patients with more severe hamstring injuries respond equally to the study procedures.

Take home messages

At worst, no difference exists in the time to return to sport after performing early lengthening for hamstring injuries. At best, the athlete performing the early lengthening exercises may return 2 weeks earlier compared to when these exercises are delayed. The early initiation of these exercises did not impact hamstring reinjury at 2, 6, or 12 months.

Reference

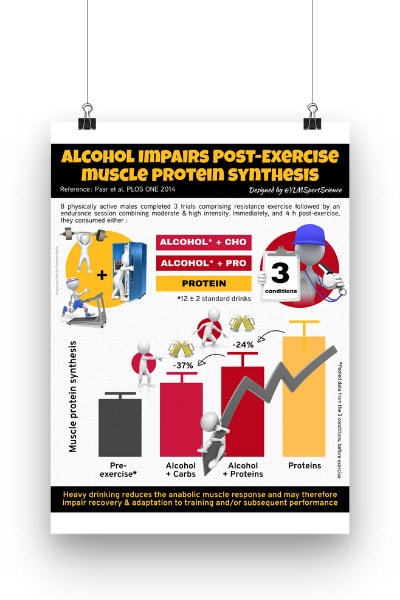

100% FREE POSTER PACKAGE

Receive 6 High-Resolution Posters summarizing important topics in sports recovery to display in your clinic/gym.